Nazi extremism in Germany led to the Holocaust—one of the most horrific state-sponsored genocides in modern history.

The word “Holocaust” originates from the Greek “holos” (whole) and “kaustos” (burned), historically used to describe sacrificial offerings consumed by fire. Since 1945, however, it has come to signify something far more sinister: the ideological and systematic, state-sponsored extermination of six million European Jews and millions of others under the brutal regime of Nazi extremism in Germany, between 1933 and 1945.

Driven by the belief in racial superiority and hatred toward perceived outsiders, the Nazi regime, under Adolf Hitler, initiated what would become one of history’s most horrifying genocides. The Holocaust was not an isolated event, but the end result of years of escalating policies rooted in Nazi extremism in Germany — from marginalization and segregation to mass deportation and industrialized murder.

Antisemitism and the Rise of Hitler

Antisemitism did not begin with Hitler. Though the term was coined in the 19th century, prejudice against Jews stretches back centuries — from Roman persecution to medieval expulsions and pogroms. The Enlightenment brought hope of tolerance, but it was not universal. By the early 20th century, racial antisemitism had taken hold across much of Europe.

Hitler, born in Austria in 1889, was shaped by a cultural climate already tainted by ethnic nationalism. After Germany’s defeat in World War I, many, including Hitler, blamed Jews for the country’s downfall. In his infamous book Mein Kampf, written during his imprisonment after the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, Hitler laid bare the ideological underpinnings of what would evolve into Nazi extremism in Germany — envisioning a Europe purged of Jewish influence and dominated by a “pure” Aryan race.

1933–1939: Institutionalizing Hatred

Once appointed chancellor in January 1933, Hitler moved swiftly. The Nazis began consolidating power, targeting political opponents first — Social Democrats, Communists, and trade unionists. The opening of Dachau concentration camp that March marked the beginning of a vast system of incarceration and terror.

Meanwhile, policies against Jews accelerated. Through the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, Jews were stripped of citizenship and banned from marrying non-Jews. Businesses were seized, professions lost. Nazi extremism in Germany meant more than rhetoric — it was lived reality, enforced by laws, propaganda, and police.

Events like Kristallnacht in 1938 — the coordinated destruction of Jewish homes, synagogues, and businesses — revealed just how quickly ideological hatred could erupt into sanctioned violence. Over 100 Jews were murdered, thousands arrested. And still, worse was to come.

Outbreak of War and Ghettoization

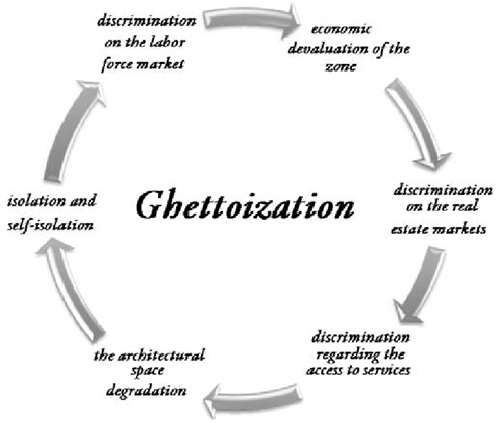

When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, the Holocaust entered a new phase. Jewish families were forced from their homes, relocated into overcrowded, walled ghettos — like the infamous Warsaw Ghetto — where starvation, disease, and despair were rampant.

Nazi extremism in Germany, now exported across occupied Europe, created captive populations controlled by Jewish Councils under Nazi oversight. The ghettos were never meant as long-term solutions; they were holding pens for something more final.

Simultaneously, the so-called Euthanasia Program targeted disabled Germans, viewed as burdens to the Aryan state. Over 70,000 people were murdered by gas, injection, or starvation. Though public outcry led to a temporary halt in 1941, the methods — and mindset — would reappear on a much larger scale.

The Final Solution: 1941–1942

As the Nazi military machine pushed eastward into the Soviet Union, mass murder escalated. Mobile killing units known as Einsatzgruppen followed the troops, executing Jews, Roma, and political dissidents. In forests and fields across Eastern Europe, hundreds of thousands were shot in mass graves.

On July 31, 1941, Hermann Göring authorized Reinhard Heydrich to begin planning the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.” This marked the formal beginning of the genocide. By September, Jews across Nazi-occupied territory were forced to wear yellow stars, a precursor to deportation and death.

Nazi extremism in Germany became more organized, more lethal. By late 1941, the SS began experimenting with Zyklon B gas at Auschwitz. What followed was a cold, mechanized campaign of extermination.

Death Camps

Between 1942 and 1945, six primary extermination camps — Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Sobibor, Majdanek, Chelmno, and Belzec — became the epicenters of mass murder. Unlike earlier camps focused on labor or imprisonment, these facilities were built for one purpose: efficient killing.

At Auschwitz alone, over one million people were murdered. Trains packed with Jews, Roma, and others arrived daily. Many were sent directly to gas chambers disguised as showers. Others were selected for forced labor, starvation, or horrific medical experiments conducted by men like Josef Mengele.

These killings were not chaotic acts of war. They were planned, budgeted, and carried out with bureaucratic precision — the ultimate manifestation of Nazi extremism in Germany, executed on an industrial scale.

Resistance, Silence, and the World’s Awakening

Though surrounded by fear and death, resistance existed. The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in April 1943 saw poorly armed Jewish fighters hold off the Nazi military for nearly a month. Revolts broke out in camps like Sobibor and Treblinka. Few escaped, but their defiance shattered the Nazi narrative of Jewish passivity.

Allied powers received reports of mass killings as early as 1942 but were slow to act. Whether due to disbelief, political priorities, or antisemitic undercurrents, the inaction remains one of history’s moral failures.

The End of the Nazi Regime – But Not the Killing

By early 1945, the Third Reich was collapsing. Yet the killings continued. Death marches moved prisoners from evacuated camps into Germany, away from advancing Allied forces. Many died from cold, hunger, or execution along the way.

On April 30, 1945, Hitler committed suicide. Days later, Germany surrendered. But for the survivors, liberation was only the beginning of another struggle — to rebuild lives in a world that had abandoned them.

Aftermath: Reckoning with Nazi Extremism in Germany

The trauma of the Holocaust — or Shoah, as it’s known in Hebrew — did not end with the fall of Berlin. Many survivors had no homes, no families. Communities had been annihilated. In 1948, the state of Israel was created, in part to provide a homeland for Jewish survivors.

The Nuremberg Trials exposed the horrors of the Holocaust to the world. For the first time, state leaders were held accountable for crimes against humanity.

In the decades that followed, Germany would undergo a long process of reckoning. Beginning in 1953, reparations were paid to survivors. Memorials, education, and public acknowledgment became central to confronting the legacy of Nazi extremism in Germany.

Conclusion

The Holocaust remains one of the most meticulously documented genocides in human history. It was not a spontaneous eruption of hatred, but the result of deliberate decisions, made possible by complicity, silence, and bureaucratic efficiency — all fueled by Nazi extremism in Germany.

To remember the Holocaust is to acknowledge how quickly civilization can unravel under ideology, how ordinary people can become perpetrators, and how fragile human rights truly are when hatred is institutionalized.

Source: Qatarajel